The Religious Art of the Muzeul Național de Artă al României

The National Gallery (Medieval and Modern Romanian Art) - one of the constituent parts of the MNAR - is really spectacular. It is housed in the former Royal Palace, and is an extensive collection. Few of the artists represented are well-known in Western Europe, but they definitely should be! There is art to suit all tastes, and you could happily spend a few hours taking it all in. Since my first visit, which was some time before we finally arrived in Bucharest, I have been thinking about the range of religious art - and in this post, I’d like to share a few highlights.

Medieval Embroidered Vestments

The Galeria de Artă Veche Românească has one of the best collections I know of embroidered vestments. These are difficult to photograph because of the reflection from the cases, but these vestments alone are worth a visit. Many of the items have retained their colour and vibrancy, and the level of detail is extraordinary. They are full of rich symbolism and you can see the love and care with which these vestments were made, all to the glory of God.

The Medieval Gallery also contains innumerable icons, Gospel books and other liturgical items. There is an impressive collection of miniature ivory crosses, and the level of detail on these is phenomenal.

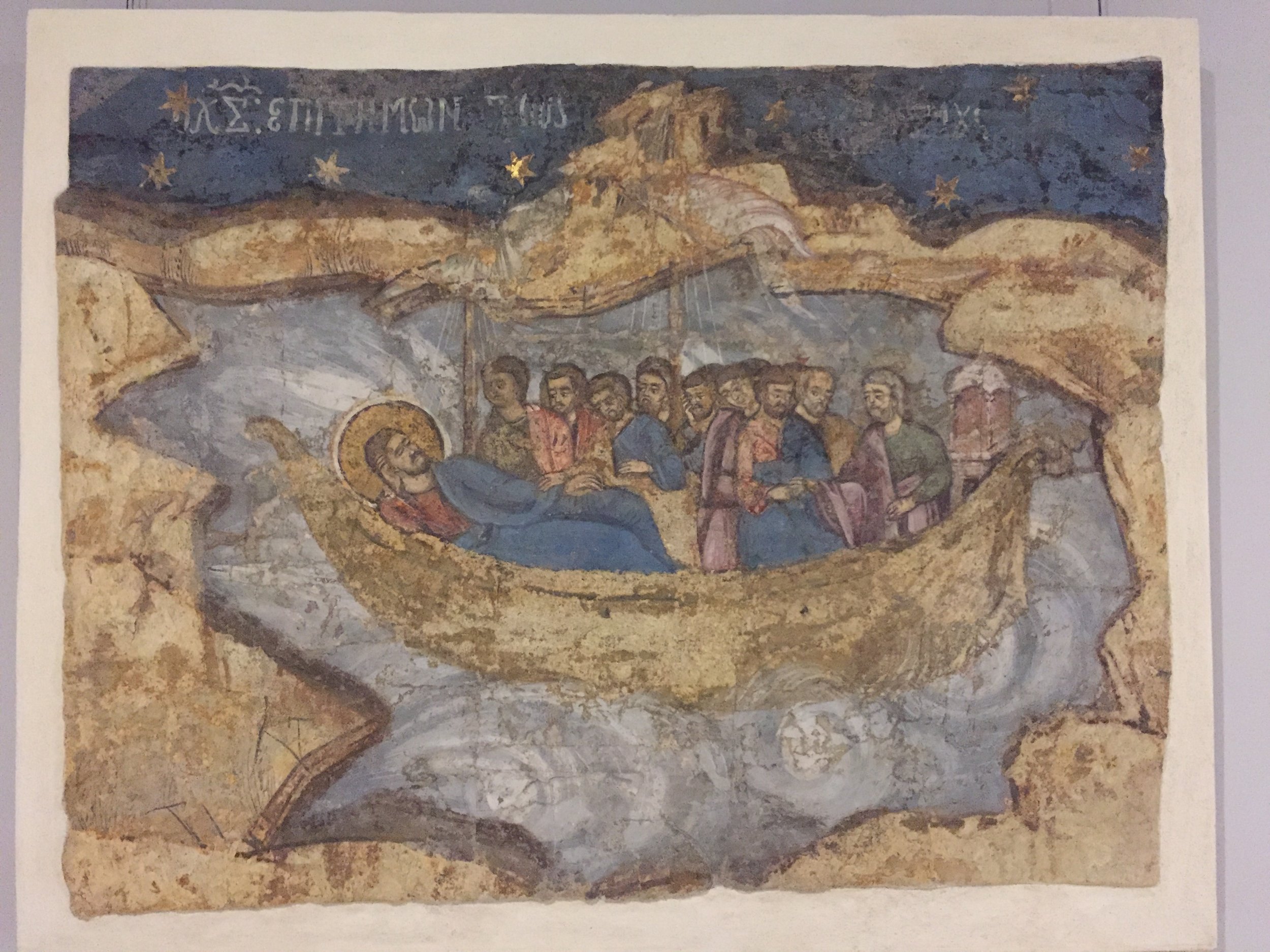

A handful of the frescoes and some of the stonework from Văcărești Monastery are preserved in a side-room of the Medieval Gallery. The monastery was built in 1716 but was demolished in 1984 to make way for a Palace of Justice that was never built. The frescoes are particularly beautiful, but they are also a reminder of the cultural destruction that occurred under the Communist regime.

A Still Life - but not as you know it!

In many ways, the collection of vestments and icons may seem unsurprising. I found that the way religious themes (with a particular Orthodox twist) continued to influence Romanian art in subsequent periods to be fascinating. One example is this painting by Constantin Dimitrie Stahi, called ‘Still Life - The Holy Water’ (1882). In Western art, still life paintings became a way of celebrating material pleasure (with food and wine), or expressing mortality and decay (fading flowers or rotting fruit). But this still life calls us beyond both of these things, reminding us of the tangibility of grace - even something as ordinary as water can be a sign for us of God’s work in the world.

Dimitrie Paciurea (1873-1932)

Paciurea is one of the most significant figures of twentieth-century Romanian sculpture. This piece, ‘The Dormition of the Mother of God’ was finished in 1912. I like the way a very conventional icon composition is rendered three dimensional. Instead of the usual crowd of apostles around her as she is taken to heaven, we are the ones that stand beside Mary and are drawn into this narrative. We become part of the scene as it is usually depicted in icons of the Dormition: a reminder that Mary’s final destiny is our final destiny too.

Gheorghe Anghel (b. 1938)

Another sculpture worth considering is this image of a mother and child, called simply in Romanian ‘Maternitate.’ The date - 1954 - may indicate the reason why it is not called ‘Virgin and Child,’ but the composition clearly recalls The Virgin Mary and the Infant Christ. The child extends his arms in the shape of the cross - an image of embrace, but also of future suffering and resurrection. The mother extends her hand in blessing, her fingers arranged in the way that Christ himself blesses in icons and which is still the way Orthodox clergy bless.

Hans Eder (1883-1955)

One of the most striking pieces of modern religious art is by the artist Hans Eder. He was born in Brasov, and studied across Germany, Belgium and Austria. In 1924, he returned to Brasov where he spent the rest of his life. A significant number of his paintings can be seen in the galleries and churches there.

This painting, ‘Crucifixion at the Outskirts of the Village’ (1924), recalls the way-side shrines of Europe - but also the way Christ’s crucifixion is both particular and universal. The man sitting lost and dejected recalls St Peter, the other figures carry on with their lives. The setting could have been first century Palestine, but we see here the continued resonance of Christ’s death for ordinary people everywhere. This was painted after Eder returned to Brasov, having fought in the First World War, and this crucifixion recalls the horror and agony of that war in the figure of Christ, as well as the way that such inhumanity is - and continues to be - quickly forgotten.

There are some really wonderful works in the collection of the MNAR, and I hope this has provided a brief glimpse at a handful of them. In the future, we will organise a church outing to the Medieval and Modern Romanian galleries to reflect on some of these pieces together!